All About Wi-Fi

This is going to be a rather lengthy article covering some pretty technical aspects of wi-fi and radio/electromagnetic waves. As usual, I'll avoid using a lot of jargon and I'll define the jargon where I do use it.

In this article, I'll discuss how wi-fi works, why it's crappy so often, ways to make it better, security considerations, and other stuff.

Please don't fret! Even non-geeks will get a solid understanding of the ideas presented here in the ways that I describe things. I'm a king of analogies, if nothing else.

We'll also discuss ionizing (dangerous) waves vs. non-ionizing (safe) waves to dispel the dysinformation that some people believe.

To start, we'll discuss a little history. Regular readers of my articles know that I love to discuss the old days...

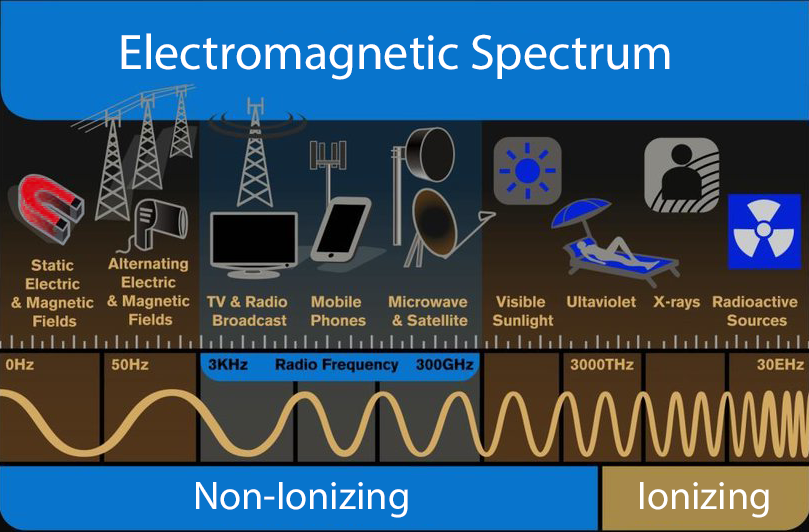

Electromagnetic spectrum showing typical use by frequency

and non-ionizing vs ionizing frequencies

Definitions preface

I need to clear up some terms first. Skip this bit if you already know all this.

A lot of people use the term "Wi-Fi" when referring to the entirety of their internet service. e.g. I often hear the following complaints from clients or read them on some of the technical forums while helping people with questions.

I can't access any websites and my TVs aren't working. I think my wi-fi must be out.

or

My computer is too slow. I need to call Socket to get faster wi-fi.

Most people get access to the internet via a physical cable that comes in the home (or office). That cable might be fiber optic or it might be shielded coax. But either way, it's a physical cable that runs in the utility easement along the street or back property line, with a tap that branches off to your home, and enters your dwelling behind a small plastic box affixed to an outside wall. That box is called the demarcation or just demarc for short.

Inside your home, probably close to the demarc (especially if fiber), will be the modem*.

* Modem means something specific whose exact definition isn't important here. Today, when we say "modem", we're usually referring to the first connected device on the customer's side of demarc (inside the premises).

For fiber optic service, your Wi-Fi transmitter is almost certainly a separate device from the modem.

For shielded coax (cable-based) service, your Wi-Fi transmitter could be part of the modem, or it could be a separate device.

Either way, Wi-Fi exists only on your premises.

It's important to distinguish Wi-Fi from the internet service itself (like Socket) because each has their own unique failure modes. e.g. You could lose internet access for reasons having nothing to do with Wi-Fi. Alternatively, you could have performance issues (buffering, dropouts, etc.) for reasons having nothing to do with your internet service.

Understanding which is pretty important when deciding if you need to call your internet provider or someone else (like me) to fix it. If ever you're in doubt on who to call, you're welcome to call, text, or email me, and I'll help you figure that out.

OK, let's carry on...

Wi-Fi doesn't mean anything

If you're over about the age of 45 or so (as of this writing, 2025), then you may have had a home stereo, or "Hi-Fi" system and you know what Hi-Fi means. For the rest of y'all raised on digital music and ear-buds, "Hi-Fi" means High Fidelity -- a high-quality component stereo system with good speakers that accurately reproduces recorded music.

Back in the 1990s, what is now called the Wi-Fi Alliance needed a brand, a name, a term for the then-new local short-range wireless protocol to be used to access the internet from our computers. So they hired a branding company and they came up with "Wi-Fi".

Thing is, "Wi-Fi" isn't short for anything -- it never was.

Yes, one could argue the "Wi" means wireless and that does fit pretty nicely. But then human nature needs to find a meaning for "Fi" as well. And that's where the "Wi-Fi" branding fails us. The term Wi-Fi was coined long enough ago that having a home stereo system, a Hi-Fi, was still fairly common. And so, because nature abhors a vacuum, people just assumed the "Wi-Fi" meant "Wireless Fidelity". It didn't then and it doesn't now.

Although "Wi-Fi" itself doesn't stand for anything, it does represent something very specific. When we say "Wi-Fi", we are referring to a specific type of wireless protocol. This protocol is used to connect laptops, smart phones, tablets, printers, TVs, and IoT gadgets like the Ring doorbell, to an on-site access-point that is itself is connected to a hard-wired modem for accessing the internet.

This specificity is important. All smartphones and some tablets have two ways to access the internet -- cellular and wi-fi. Both ways are wireless, obviously, but only one is called "Wi-Fi". Understanding that difference is pretty important.

HAM

I'm an amateur "HAM" radio operator. Another word that isn't short for anything. I hold a license from the FCC (a federal agency) that grants me the privilege to transmit powerful radio signals (voice, usually, but could be Morse code or even digital data these days) that can reach the other side of the world under the right circumstances. Having a HAM radio license (or "ticket" as we HAM's say) means I studied-for, passed several exams, and understand a number of laws about radio waves. Both laws of man and laws of physics.

A wi-fi router is just another radio transceiver, albeit highly specialized. So combined with my networking know-how, I've got a pretty good understanding of how wi-fi routers work and why they don't.

Save on your phone's data plan

I've visited many clients who did not know their smartphones could access their home wi-fi networks. Their laptops and TV sets were connected to the wi-fi, but not their phones. Since the phone could access the internet (via cellular) then it didn't occur to these clients that anything else needed to be done, e.g. connecting to the home's wi-fi network. After all, the phone can get online, so what else is there to do, right?

Why is that a big deal? Because using cellular on your phone chips away at your monthly data allotment. If you enjoy data-intensive activities on your phone (watching videos, especially) but even sharing photos or streaming music, then you can easily hit your data allotment for the month and incur additional fees from your cellular carrier (Verizon, AT&T, etc.)

But if your phone is connected to a wi-fi network, then all that transferred data comes through the wi-fi instead. That means you aren't using your cellular data while you are at home. If you regularly exceed your cellular data quota, there's a good chance you aren't connected to your home wi-fi while at home.

Also, you may have a weak cell signal inside your home if the closest tower is farther away. But your wi-fi, if properly specced and installed, can be strong in every room, That means much better phone performance.

If you don't have wi-fi at home, but you do have internet, then a wi-fi device can be easily added and there's no additional monthly expense. Just a one-time cost for the device itself. You could recoup that cost pretty quickly by not going over your cellular data plan.

Nosy Neighbors

It's critical that your wi-fi network has a password to prevent your neighbors from surfing on your signal. You don't want the neighbor across the back fence surfing for child porn on your internet connection! Wi-Fi doesn't work well for more than a few hundred feet, but it may work well enough for your immediate neighbors to use. So lock it down using a password.

Guests and medicine cabinets

It's a bit of a trope that guests like to snoop through their host's medicine cabinet to see what private health issues they can suss out. Well, if you let your guests on your wi-fi network, they could possibly do the same thing if they are tech-savvy enough: Snooping around your network and possibly onto your computer. Or any malware that might be on their laptop could possibly infiltrate your network.

How to avoid that? Some wi-fi routers have a "guest mode" that is designed expressly for your guests and visitors. The special mode allows the guest to reach the internet only. They are blocked from accessing any other device on your network. This way, your network remains secure from snooping and possible malware infection. The guest mode wi-fi has its own password so you can freely give it to your guest without disclosing your private wi-fi password.

Some routers don't have a guest mode. And even the ones that do, it's usually disabled by default. An I.T. geek like me can enable that for you by accessing the router's management console. I can even to that remotely! Or if your router lacks that feature, I can install one that does.

This is actually pretty darned important. If you have guests or visitors that want to access your network, it's really important that they use an isolated guest network. Allowing guests on your private wi-fi network is akin to needle-sharing by junkies. Yes, it could be that bad.

Radio roadblocks

The high microwave frequencies (2.4 GHz and especially 5 GHz) used in wi-fi are easily absorbed by nearly everything. So, attenuation (weakening) of the radio waves by obstacles in your home or office is a big problem. That means absorption by furniture, appliances, walls, floors (for a multi-level home), and even people and pets. Distance also plays a role. Getting a bigger, badder wi-fi router doesn't help, either. In fact, it'll only makes things worse! First of all, there are max legal power limits that manufacturers cannot exceed. But aside from that, higher power often decreases performance! More on that in a bit.

Other ways to reduce absorption is to place the wi-fi router as high as possible, such as the top of a tall cabinet. I know, I know... How to possibly pull that stiff coax cable to the top of some cabinet in next room that's nowhere near a cable outlet. More on that down below as well!

But think about it. Everything in your home ultimately starts at the floor, because gravity. The highest density of stuff occurs at ground level. As your point of view rises farther above the floor the view becomes less obstructed. Higher up, near the ceiling, it's likely a much clearer shot all over the house except for the walls.

Shouting in a loud restaurant

Imagine yourself in a packed restaurant or bar (I'm thinking Barred Owl here!). How loud do you have to talk to be heard by the person next to you? If you start speaking louder to overcome the din around you, well, everyone else will do the same thing. Pretty soon it's deafeningly loud and no one can understand much of anything. Man, I hate crowded restaurants for this very reason.

Wireless internet devices operate in a "collision domain". Say what? Unlike the restaurant mentioned above where everyone is loudly talking (and not understanding anything), wireless devices cannot do that. If two or more proximate wireless devices start transmitting on the same channel at the same time then a collision occurs and neither device is heard.

Each colliding device then stops transmitting (talking) then waits for a random number of microseconds (the backoff period) before trying again. The idea being that each device will choose a different random wait time so the likelihood that both will start retransmitting again at the exact same time is low. This works pretty well when there's only a few devices involved and traffic levels are low. Traffic is data being transmitted.

But what happens when there's a lot of wireless devices and some of them are bandwidth pigs? I'll spare you the math here, but as more devices come online and wi-fi traffic levels increase, the collision rate expands geometrically. At a certain point, the rate of retransmission snowballs, swamping channel capacity, resulting in a dramatic drop off in throughput -- that noisy restaurant! This is called congestion collapse and occurs when retransmission hits about 50 to 60% of available capacity. Not good!

Crowded Airspace

It's not unusual for (some) homes to have a dozen or more wireless devices when you consider all the gizmos available today. In addition to the usual laptops, phones, and TVs, we also have a plethora of mostly-pointless ("Internet of Things") wi-fi gizmos such as thermostats, baby monitors, door locks, ring cameras, and a wide range of appliances like wi-fi coffee makers, ovens, stoves, dishwashers, laundry machines, refrigerators, and likely many more. And the same thing goes for all your neighbors as well.

Ever see one, two, or even a dozen of your neighbor's wi-fi networks on your laptop or phone? Even though your wi-fi network and your neighbors' are separate and secure (that's what the wi-fi password does), they are still sharing the same radio channel airspace. If you can see your neighbor's wi-fi name, then all their wireless gadgets are also within radio visibility as well. And vice-versa -- all of yours are within radio visibility to their network. Depending on channel availability and signal strength, that means your devices and their devices cannot both talk at once, even on their own separate, secured, and isolated networks!

If you live in close quarters with your neighbors, such as an apartment building or condo, or even single family homes that are packed in close together on small lots, then the effect above can be multiplied by far more wi-fi networks. It could be dozens!

Now, factor in devices that are high-traffic like streaming video (Netflix, Youtube, etc.). Your streaming device could be receiving so much traffic that the rest of your network (including the offending device) is suffering as a result. Throwing in more power or buying higher speed bandwidth from your ISP isn't necessarily the answer, either. And due to radio visibility between nearby homes, your neighbors streaming TV could affect your network!

And if all the foregoing wasn't bad enough, factor in devices that aren't intelligent and "wireless aware" like your microwave oven or some cordless phone models. Now throw in multi-path issues, signal harmonics, and signal absorption, etc. These are intrinsic problems with wireless devices.

Maybe you are wondering how your network can be secure if your wi-fi traffic can reach your neighbor's home? Or why several homes, each with their own network name and password cannot all use the same channel?

Think of a room, large bedroom-sized say. In my analogy, that room is like a wi-fi channel. Inside this room are two or three groups of people, maybe 3-4 persons per group. Each group speaks their own language that the other groups don't understand. If all the groups are talking at the same time then it may be difficult to focus on the others in your group because there's too much noise.

Now suppose the groups take turns with only one group speaking at a time. It's a lot easier to communicate now with others in your group without a lot of chatter from the other groups. And it doesn't matter that the other groups are sharing the same room (channel) because they each speak a different language (password). This is how a limited resource can be visible-to and shared-by several parties yet still maintain privacy.

Another analogy is if everyone that shares an old-fashioned party line each spoke a different language. The nosy neighbors can listen in all they want but they won't understand anything. But what they cannot do is use the party line at the same time.

2.4 GHz vs. 5 GHz vs. 6 GHz

"GHz" = Gigahertz. "G" or Giga means billion. "Hz" or Hertz* is the word denoting the frequency of radio waves. 1 Hz is one sinusoidal cycle per second.

The US has three main frequency bands** that are used by wi-fi routers, each with their pros and cons. All wi-fi routers sold today offer 2.4 and 5 GHz, and many are starting to offer 6 GHz. The 6 GHz band is fairly new and not widely deployed as of this writing. It has operating characteristics similar to 5 GHz. Here's a rundown of pros and cons of each band.

* It's called Hertz in honor of Heinrich Rudolf Hertz, a German physicist who, in 1887, first proved the existence of electromagnetic waves.

** A band is a defined frequency range in which individual channels reside. e.g. Your car radio has AM and FM bands. Each of these two bands have lots of channels and behave differently, having their pros and cons. e.g. FM sounds better but AM can work farther at a given power.

2.4 GHz - Pros

- Wider device support - Many printers and IoT gadgets still only support 2.4 GHz. Not a big deal since printers and most IoT gadgets are fairly low traffic devices.

- Better penetration of obstacles - Walls, furniture, appliances, and distance don't affect 2.4 GHz as much. Mind you, this same penetration advantage can work against you if your neighbor is on the same channel.

2.4 GHz - Cons

- Inherently slower band even with no interference from other devices

- Fewer channels resulting in more overlap which leads to collisions which means poorer performance

- Far more crowded in any event. There's simply more devices on 2.4 GHz than 5 GHz (though that's changing)

- Interference from certain cordless telephones, microwave ovens, and other non-friendly devices on this widely used band

5/6 GHz - Pros

- Much faster when signal strength is decent, often a 10 to 20x improvement in speed

- Less crowded though more people/devices are starting to use it

- More channels available, resulting in less crowding per channel

- Shorter range means less interference from other distant 5 GHz devices, like your neighbors

5/6 GHz - Cons

- Many printers and IoT gadgets do not support 5/6GHz. Some are starting to but it's not universal yet.

- Shorter range can also be a con, especially if you're in a fairly isolated area where neighbor interference isn't a concern.

5/6 GHz is more susceptible to attenuation from environmental obstacles. That's actually a pro in that it helps prevent interference from neighbors. It's a con when it limits connectivity in your own home. But on balance it's good because you can mitigate your own limited range issues by using additional access points or a mesh network. But you can't do much to limit interference caused by a neighbor.

Regarding printers being on 2.4 GHz and your other devices on 5 GHz: From a networking perspective, this matters not. Devices on these two bands and those that are hardwired can all communicate with each other, no problem.

Let's clarify something: 5 GHz and 5G (like on a smartphone) mean completely different things!

- 5 GHz refers to a specific frequency band (radio waves). Some wireless routers include the letters"5G" on the wi-fi name to signify that it's 5 GHz. That's an unfortunate use of the term since it confusingly conflates "5 GHz" with "5G".

- 5G (on a smartphone) means "fifth generation", which is strictly a marketing term referring to a newer class of high-speed cellular data that is the standard today in the US and elsewhere. There is no intrinsic technical meaning to this term. It's just marketing.

The gold standard

The above should convince you that RFI (Radio Frequency Interference) is a thing. Hard wiring fixes that! Hard wiring always offers a superior connection and should be used whenever possible.

So what to do? There's several things to do here, each contributing to reducing wi-fi traffic.

Ways to reduce wi-fi traffic:

- Hard wire your streaming TV or player appliance like Roku or Apple TV. If you do nothing else, just removing a streaming device from the wireless ecosystem will help.

- Hard wire all stationary computers including towers, AIOs (All In Ones), and even laptops while they're being used at their main location such as a desk.

- Hard wire your printers that have an Ethernet port.

- Hard wire all gaming consoles. This will reduce lag as well when playing in multi-player mode with others

- Reduce or eliminate stupid IoT gadgets from your home. Aside from reducing the wireless footprint, you'll eliminate some security vulnerabilities as well. For more on IoT, see ~~Internet of Things

- And for all that is good and holy, please don't buy wireless security/surveillance cameras! Install only hard wired cameras! A doorbell cam might be the only exception.

In short, reserve your precious wireless spectrum for smartphones and tablets.

Tearing down the walls

OK, I'm sold! But how do I hardwire my TV and main computer? Hardwire means an Ethernet cable from your router (there are ports on the back just for this) to your TV, main computer, whatever else. Yes, running cables is a PITA and may require some creative solutions. Or you could hire a cable monkey to do it. But I absolutely guarantee that you'll have a better streaming and internet browsing experience if you do this. And with fewer devices on your wireless network, those that remain wireless should perform better as well (depending on your neighbors).

Homes built more recently, since the mid-aughts, may already be wired for Ethernet.

For an office environment, it's an absolute no-brainer. Offices should be hardwired, period.

Other wireless issues

Maybe you don't have a ton of wireless stuff. But perhaps your home is large and you just want a decent signal for your phone or tablet everywhere in your home. There are solutions that can reliably blanket your home with a good signal. As I said higher up, wireless signals are attenuated by many things in your home.

For larger homes, e.g. greater than 2,000 sq/ft, especially if all on one floor (large footprint), it can be difficult getting a decent wireless signal to all areas, no matter how powerful the wi-fi router. There are several ways to accomplish this.

Ways to improve wi-fi signal throughout your home:

- Hardwiring additional wireless access points strategically located within your home

- Ethernet over power line transceivers, with optional additional wireless access points

- Wireless mesh system

The newest kid on the block are wireless "mesh" systems. A mesh uses multiple nodes or pucks (three is common) strategically placed throughout your home. Each node is a wi-fi access point that provides a strong signal in that part of the home. The node relays wi-fi traffic back to the main node that's connected to the modem.

The mesh nodes are also attractive to look at. Or at least they're not ugly. They're small, usually all white, have few or no markings, have no visible antennas, and is inoffensive on an end table or top of a cabinet.

Avoid the inexpensive ($30 or so?) "wireless repeaters" that plug directly into a wall outlet like a nightlight. These often have two short antennas attached. This type of repeater is not the same as a proper mesh system and are suboptimal because of how they repeat the signal.

Are Wi-Fi and other radio waves dangerous?

NO!

Now let's discuss why. This discussion can rapidly spiral into electromagnetic physics, so I'm going keep it simple. Sorry for being so lengthy on this. But this a controversial topic so I want to make it readable for all, regardless of someone's understanding of physics.

Radio waves, the kind used to transmit voice, images, and other data (TV, AM/FM radio, mobile phones, w-fi, and all the rest) are a type of non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation.

Even the visible light you see is a type of non-ionizing radiation. Yes, even light! Your eyes are, in fact, a type of biological antenna that is tuned (sensitive) to a range of electromagnetic waves. In this case, "light" waves instead of "radio" waves. The waves are the same, just different frequencies.

What does non-ionizing mean? It means the electromagnetic waves emitted by the radiator (antenna) lack the energy to dislodge electrons in the atoms or molecules they transit. Molecules, for examples, that your body is made of.

Because they are non-ionizing, these waves cannot structurally attack or change the atomic and/or molecular makeup of things in our physical world. The waves can pass through, but they do so without harming the matter being transited. Just as shining a flashlight through a window doesn't damage the glass.

There are also ionizing electromagnetic waves. Ionizing means the emitted waves can damage atoms or molecules and eject their electrons. These dislodged electrons are called free electrons. Because electrons tend to seek stable configurations (they don't like to float around), they’ll quickly reattach to nearby atoms or molecules -- often where they don’t belong. This creates free radicals, which are atoms or molecules with one or more unpaired electrons, making them highly chemically reactive. That's bad for biological tissue.

Ionizing radiation includes UV-C rays (from the sun, usually, though most of that is absorbed by the ozone layer), x rays, and gamma rays. Ionizing waves have the energy to structurally damage atoms and molecules, including biological DNA. But these waves only exist at frequencies far, far higher than any man-made radio waves that are used for communications -- many orders of magnitude higher.

Simply put, the electromagnetic waves we use for communications are not dangerous.

And don't let that word "radiation" spook you, either. The strict definition of radiation is simply "energy emitted from a source". e.g. A pocket flashlight radiates light. A "radiator" in your home radiates heat. In this case, it's built right into the name of the appliance. Thus radiation refers to all emitted energy, only a small slice of which is dangerous -- the ionizing radiation discussed just above.

What about my microwave oven? That uses electromagnetic waves in the same frequency band (2.4 GHz) as my wi-fi router and it can cook food! That sounds dangerous!

OK, let's talk about that.

Microwave ovens do not emit ionizing radiation. It heats up food by concentrating a high amount* of electromagnetic waves that penetrates the surface of the food, causing water and other polar molecules within the food to mechanically vibrate. It does not break them apart!

* A typical microwave oven has a 1,000+ Watt emitter, inside a radio-reflective (Faraday) enclosure, and mere inches away from the food.

By comparison, the legal max power for a wi-fi router is 1 Watt -- itself already three orders of magnitude less than your microwave oven. And it doesn't stop here. The strength of electromagnetic waves drops at the inverse square of the distance from the emitter. e.g. When your distance from the (wi-fi) transmitter doubles, the strength drop quadruples.

The inverse square law is why a bonfire can feel pretty hot when you're up close but dramatically drops off if you backup just a few steps.

So, your wi-fi isn't cooking your skin or scrambling your brain.

Then how do microwaves cook food?

Water has a resonant** frequency of 2.45 GHz which, uncoincidentally, is the same frequency as a microwave oven. This allows the water, and food which is mostly water, to easily vibrate mechanically thus quickly heating it up. The fundamental makeup of the food's atomic structure remain unchanged.

The mere act of heating up any food, regardless of how you heat it up (microwave oven, regular oven, stove top, gas grill, whatever) can change the food in certain benign ways, such as softening the food, releasing aromas, possibly browning, but there are no fundamental changes to the molecular makeup of that food. It just heats up.

Now then, burning food to a crisp does cause molecular changes through combustion effects, creating compounds that aren’t great to eat. That’s why the blackened grill marks on a steak aren’t ideal to ingest. This effect can happen with any cooking method, but it’s more likely with high-heat methods like grilling or pan-frying than with microwaving, which doesn’t reach those high surface temperatures.

In other words, conventional heat-based methods cook from the outside toward the core, while a microwave oven heats food more uniformly throughout its volume. The chemical changes from heating are the same either way.

** What does “resonant” mean? It refers to the natural frequency at which a material or structure tends to vibrate when energized. When something vibrates at its resonant frequency, it does so more intensely -- often with dramatic amplification.

Ever sing in the shower and notice that one particular note sounds much louder than the others, even though you didn’t raise your voice? Almost like the walls are vibrating? That’s resonance. You’ve hit the resonant frequency of the shower enclosure, causing the walls and air to vibrate in sync with that note, amplifying it.

Resonance is a fundamental and natural phenomenon found in everything from musical instruments to bridges, microwave ovens, and even molecular chemistry.

Why should I believe you?

Ah, yes, this falls into the "5G" realm of conspiracy theories. That brand of anti-science conspiracist is not likely to believe me even though I've studied electromagnetic phenomena (licensed HAM radio operator, remember?) and have a better understanding of it than most people.

Alas, I can only do so much. I've tried disabusing conspiracists of preposterous notions that the COVID vax makes people magnetic, contains tracking microchips, that homeopathy is legitimate medicine, or that climate change is some leftest hoax, all to no avail. It's tiresome, really.

But those with an open mind, who are hungry for new learning and have a correctly functional prefrontal cortex, they can easily verify the statements I've made above by performing their own searches using Google or whatever search engine one prefers. That is, of course, if one has the media savvy to avoid the websites and social media that spew conspiracy-laden bullshit.

OK, that's a wrap

If you made it this far, thank you for reading. You now know more about wi-fi and radio waves than 90% of the population. You'll be a smash at your next party.

We've covered a lot of topics here regarding wi-fi, all of it pretty technical. If you are having intermittent internet problems, especially with TV buffering and apparent speed, then there's a chance your wireless environment is the cause.

I can help diagnose and fix that.